Deep POV is a fiction writing style that aims to remove the narrative or psychic distance between the reader and the point of view character — think first person shooter style. The goal is to completely immerse the reader in the character’s emotional experience, in a way that feels immediate. When done well, deep pov will grab your reader by the throat and not let go. But, deep pov leaves no place for weak writing, poor plotting, or under-developed characters to hide. Deep POV is the black-belt of fiction writing!

For the summer, I’m working on a series of posts that will look at different emotions. Emotions are really the heart of deep POV. Let’s take a quick minute to look at the role of emotions in deep POV and why it’s worth a whole summer of posts.

Omniscient POV

If you think of works written in omniscient pov, the narrator/writer voice tells the reader a story about one or a group of characters and shares everything the characters think and feel. Nothing comes to the reader directly from the character apart from spoken dialogue. An example would be Lord of the Rings.

Objective Third Person

This is still the writer/narrator telling the reader a story about one or more characters, but usually this style leaves out the emotions. It’s objective. You’ll get the character’s thoughts and actions filtered and interpreted through the narrator, but not very often will the narrator voice delve into how the character feels.

Limited or Close Third Person

This is the writer/narrator telling the story about ONE character at a time. That’s the big difference. There’s typically only one to three point of view characters, and you only get one pov at a time. The character’s thoughts and actions and emotions are filtered and summarized through the narrator, however — limited third person makes room for direct thoughts. Many like to italicize the thoughts of the characters to differentiate them from the narrator/writer voice. There are many newer writers who believe they’re writing in limited third person and they’re actually writing in objective third. Ask yourself what place emotions have in the storytelling?

Deep POV

Deep POV shifts everything, that’s why it can be so hard to learn. Every word on the page (every action, thought, feeling, bit of backstory, element of setting, every description — all of it) comes to the reader directly from the character. There is no author/narrator/writer voice to filter, describe, summarize or explain what’s going on. Hear me when I say this: N O N E. And the thread that makes deep POV really explode off the page, are the character’s emotions.

SHAME VS GUILT

If you google this, psychology sites are going to inundate you with a flood of conflicting answers. In fiction, there are primary and secondary emotions. Primary emotions are the gut reaction, without-thinking, knee-jerk responses to events, conflict, people, etc. Secondary emotions are the reactions to the primary emotions. Depending on the character and the situation, many emotions can be either primary or secondary (for the purposes of fiction), but some are almost ALWAYS secondary emotions. And shame is one of those (anger is another). Shame is almost always a reaction to another emotion.

Guilt and Shame are emotional cousins but there are distinctions — and the labels might not be particularly helpful for your writing but understanding the differences can be. Guilt can be good for us when it pushes us to change (our thinking or behaviour). Guilt can lead to regret, can lead to righteous anger, etc. Guilt says “I did a bad thing.” When I threw a ball in the living room and broke Mom’s favourite antique cup and she cried — I felt guilty. I won’t ever throw a ball in the house again.

False guilt is when we have negative feelings (real or perceived) about our own thoughts or actions, but you really had no control over those events or actions. I was texting in the backseat when the car hit a patch of black ice and we hit a tree. If I wasn’t texting in the backseat, Dad wouldn’t have had that accident.

Shame is not about something we did, it’s about who we are. Guilt says I did a bad thing. Shame says I’m a bad person. Shame can be placed on us by others and we can place it on ourselves through real or imagined perceptions of how others see us. Shame can arise from a loss of status or identity. You can’t just change your behaviour to get out from under shame like you can guilt. With shame, who you are is the problem. I am overweight, so that means I’m ugly, unlovable, and lazy. Or I was molested so I’m dirty and broken and unlovable.

Do you see the difference? Shame is debilitating.

Shame seems to be one of those really universal emotions that I don’t see writers delving into too much in fiction — which is a “shame” (hahaha – see what I did there) because it’s such a powerful, compelling, and rich-with-complexity emotion. This can (and in many cases should) be part of what drives characters to their absolute lowest moments.

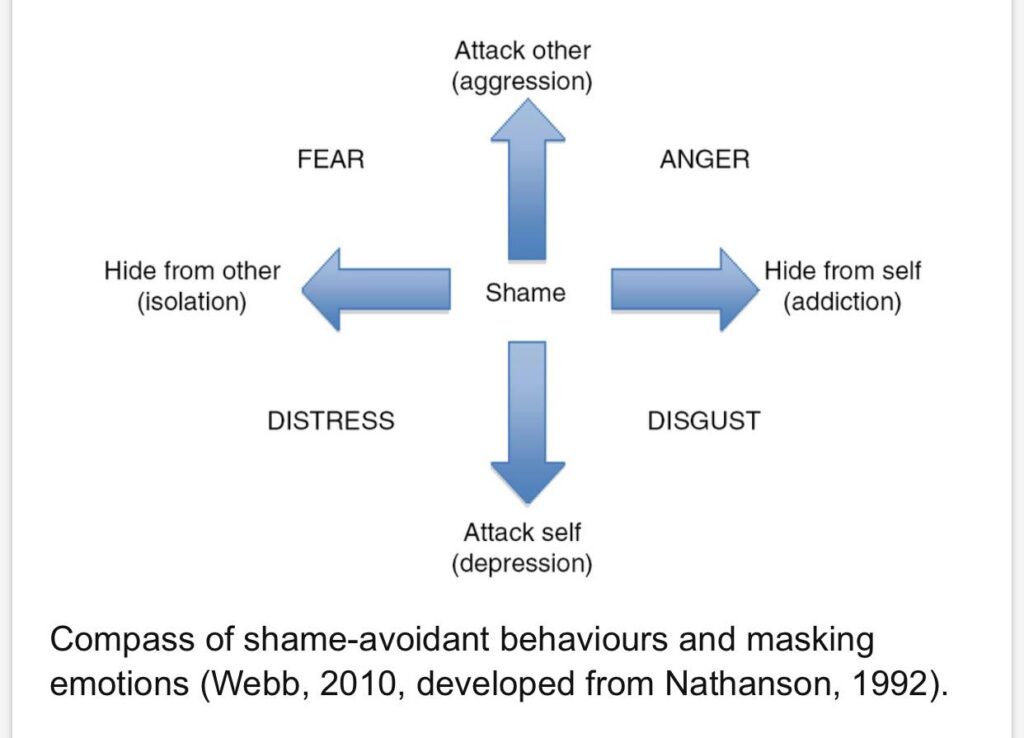

This is a really awesome graphic that shows the many ways we try to shake off shame. Shame is one of those emotions that we carry around, it sits like a rock on our chests, and we can’t get out from under it by avoiding it, or being logical, or ignoring it. The only way out from under shame is to acknowledge its concerns, and answer those concerns. Those who struggle with perfectionism are more prone to shame. Those who care (too much) about what other people think of them, are more prone to shame. Shame is the shadow that relentlessly haunts trauma victims and whispers — it was all your fault — you’re a failure — there’s no hope.

Writing Shame In Deep POV

Because there’s no author/narrator voice to summarize, explain, or narrate what’s going on inside your character, you must capture the emotions with enough realism and immediacy that the reader can understand not only how your character feels but why those emotions are driving their thoughts and behaviours.

The unique blend of primary emotions that fuels the shame will be unique to your character. That unique blend will carry with it different triggers, different coping mechanisms, etc. You can learn more about primary and secondary emotions here and more about coping mechanisms here.

Someone who feels shame about being overweight and unable to lose the weight, will have different triggers and sensitivities than someone who feels shame because they were abused – for instance. The actual emotion will feel the same, but the primary emotions behind it may be different. The intensity may be different. The reactions to the shame will be different. The way it causes disfunction or change will be different.

The key to deep POV is specificity and particularity. Put the reader in the scene with the character, in their shoes, inside their head — keep no secrets. Then the WHY behind the character’s thoughts and actions becomes clear without you needing the writer/narrator voice to TELL the reader what’s going on.

Don’t Be Afraid Of Complexity

So many times, I’ve encouraged students to delve deeper into the emotions in a scene. What ELSE is going on here? They create these dynamic, powerful, tension-filled events, and the character is simply afraid, or simply frustrated or simply angry. NO! Life is never that simple, is it? We have emotions that conflict, that amplify, that contradict one another. Emotions can be fleeting or last a lifetime. Get curious about that.

Ask not only what ELSE is the character feeling, but explore what a better person would do in this situation? Why can’t they be that person? What would a stronger person do ? What keeps them from doing that? Ask them what they think they SHOULD do in this situation? Why aren’t they doing that — OR — why isn’t that enough?

Shame is one of those emotions that should add this sort of complexity for readers.

Are you using shame in your writing? Do you find it easy or difficult to write shame really well?

Lisa, this was a great post and so helpful.

I am the kind of person that learns fster by being showen, please make examples; even bad ones in half jest are fine. Thanks!